History of VW

100 Years of Motoring and the Volkswagen

Why Is The Wolf Standing On The Castle?

Der Schwimmwagen Story

Wolfsburg 1945-1946 1

Wolfsburg 1945-1946 2

Wolfsburg 1946-1949

The Evolution of the VW Symbol

Ferdinand Porsche – Versatile Genius

The Denzel Sports Car

KdF-Wagen Sparkarte

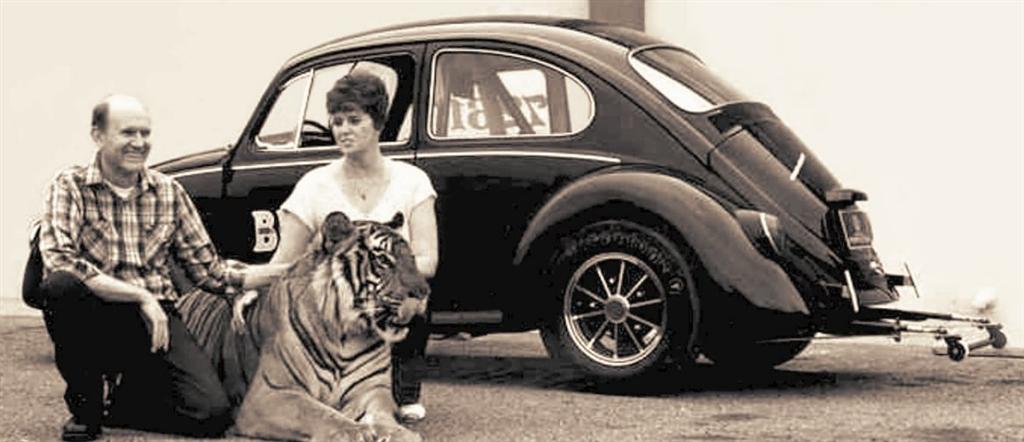

Flashback – Gene Berg

East Germany’s Finest – They’re Volkswagens

NSU – Who?

The Horch and Wanderer Story

The Only REAL Auto Unions

VW’s Early Years

Kübel Bungle!

Volkswagen – The Fab Four

The Link With Tatra

Cootamundra VW History

The Powertune Story

Obituary – Ivan Hirst

Charles Lindbergh’s VW

The KdF-Wagen

100 Years of Motoring and the Volkswagen

By Boris Orazem

February 1986

On the 29th January 1886 a German engineer and inventor, Karl Benz, applied for a patent for a gasoline powered "motor car", little more than a three wheeled buggy. A lot has happened in the following ten decades of motoring, from a vehicle that was unreliable, hard to drive and manoeuvre, and next to impossible to start, especially in bad weather. In the early days a lot of manufacturers sprang up all over Europe and significantly improved the breed to a point where one could virtually crank the motor and reliably go for a country drive. One such example was De Dion Bouton who also sold engines to other auto makers included Renault. But this pleasure was reserved for the wealthy few that could afford the purchase price and possibly the services of a private chauffeur.

The next decade saw even more refinements and more manufacturers in Europe, England and USA. But it was Henry Ford that revolutionised the industry and brought the car to the masses with the Ford Model T.

During the great depression not as many cars were sold, and the more luxurious, small volume marques were either integrated or went under.

After the depression and before the Second World War, realisation of making cars smaller, more economical and generally more refined has come about. By this time there was also a prototype on the drawing boards, the future of which its designer, Dr. Porsche, did not envisage. That, of course, was the legendary VW Type 1 as we know it now.

World War II intervened and most of the world production centred on the vehicles for military purposes. In Germany the promised 'Peoples Car' never eventuated, but was instead modified to suit the regime of the time into Kübelwagens, Schwimmwagens, Kommandeurwagens and other variations. After the war the devastated VW factory was rebuilt and from there on grew to be one of the biggest car manufacturers in the world. In 1973 the Type 1 outsold the T-Model Ford as the largest selling one model car at over 16 million units.

At the 100th anniversary of the motor car, and the "WHEELS 1985 Car of the Year Award" presentations held on 29th January (won by the Mitsubishi Magna), the Editor of Wheels Peter Robinson requested that my 1953 Oval Beetle represent the 1946/1956 decade of motoring. I gladly accepted and was honoured to be asked. Other cars of the parade (and each representing ten years) were: 1889 Benz, a priceless masterpiece; 1903 De Dion Bouton; 1914 Rolls Royce; 1926 Model T Ford and strangely yellow in colour; a very advanced 1937 Citroen Traction Avant; 1936 to '46 WW2 US army Jeep; then of course the Volkswagen and appropriately so, as these were the years in which the Beetle left the biggest impression on the buying public through its many trials successes. Next was the Morris Mini, another VW (this time a Golf) and finally a Honda Accord.

The parade was held in front of some 300 journalists, car factory representatives from here and overseas, and several other car buffs. I hope they all enjoyed looking at the history in front of them as I know I did. There was at least one Japanese gentleman taking photographs of the Beetle from all angles, maybe they are thinking of producing replicas? NOT A BAD IDEA AT ALL.

Why is the Wolf Standing on the Castle?

By Bill Rinker

February 1987

Before 1938 there was no Volkswagen factory, and no Volkswagens. In the place where they both originated, there was only a castle and lots of open space in an area called the Lunenburg Heath in northern Germany.

Now in the olden days, European open spaces were considered perfect for marching armies, so in the year 1431 the Schulenberg and Bartensleben families built a castle to keep the louts off the lawn. An emperor named Lothair had given them the land in the year 1135. No one seems to know how he acquired it, but no one challenged his right to give it away.

There must have been no shortage of people who thought the real estate showed rear potential for development. Once circa-1584 account states, “…in particular, the von Schulenbergs and the von Bartenslebens were the true captains of men…the noble lord Otho took the field against the Junkers…nor was any of them strong enough to confront the proud young lion. But he routed them again and again…”

So, why wasn’t the place called Lowenburg (Lion’s town)? No one knows, but perhaps it was a good thing since it avoids confusion with a famous beer that originated in Bavaria.

Anyway, the Schulenbergs and the Bartenslebens continued to fend off assorted hordes until 1938, when they failed to fend off appropriation by the Nazis of the land on which the mile-long VW headquarters and plant would be built.

After World War II, as a town grew around the factory, it became known by the name of the old castle which had survived centuries of battle – Schloss Wolfsburg.

That was in 1945, and the city officials decided their town should have a crest just like every other German city, most of them hundreds of years older than this pup of a town.

So, the town artist got to work. He put the wolf on top of the castle. He added some wavy lines to symbolise the Aller River, which flows nearby.

The castle, which still exists on a grassy hill behind the VW factory, has been restored as an arts centre and tourist attraction, and will probably last another five hundred years. The crest, once used on Beetle steering wheels and bonnets, will continue to be almost as representative of VW as the encircled VW trademark. Our Club VW logo is an Australianised version of the Wolfsburg crest, with a wolf on the Harbour Bridge.

Did you know, incidentally, that the encircled VW design originated as a doodle on a beer coaster? It did, but that’s another story.

Both the crest and the VW logo are sensible, solid designs. But that makes sense when you think of the cars they represent.

Der Schwimmwagen Story

By Greg Figgis

May 1987

The history of the Schwimmwagen goes back to 1932, when Hans Trippel, a German industrialist, unveiled a prototype amphibious car with four-wheel-drive and a four-cylinder Adler engine. Of course Trippel’s amphibians were sporting vehicles, just as the gliders being used by the pre-war gliding clubs were playthings. But as war clouds gathered, the playthings were rapidly converted to military use.

After the fall of France, Trippel took over the famous Bugatti plant and used Bugatti’s tools to produce Opel-powered Trippels, but it was obvious to the German High Command that a less expensive model was needed.

The next step was to order Dr. Porsche to design an amphibious version around the same mechanicals as the Kübelwagen. In fact, the first batch of Schwimmwagens were called Porsche 128 models. The Type 128 of 1940 was designated the Model A and shared the Kübelwagen’s 2400mm wheelbase.

However, the Waffenamt (German War Dept. Weapons Supply section) now demanded that military vehicles should possess an engine developing a minimum of 25 PS (hp).

Consequently, the engine’s cubic capacity was increased from 985 to 1131cm3 and horsepower from 22 to 25. This was achieved with a minimum of modification by increasing the bore size from 70 to 75mm.

The Schwimmwagen was fitted with a five-speed gearbox, four-wheel-drive being operated when fifth gear was engaged. The suspension was torsion bars front and rear, located outside the hull and sealed with rubber boots, and these could be lubricated with the ‘Bijur’ one-shot lubrication system, also used by Rolls Royce and several American car manufacturers. The first models were a sealed, door-less hull and were capable of carrying four soldiers. After the Type 128 came the Type 138, Model B, and at the end of 1942 the Type 166, Model C. These later models had doors fitted to them. They had a smaller, 2000mm wheelbase and were also lighter at 910kg, compared with the Type 128’s 950kg.

Like the Kübelwagen, the Schwimmwagen used hub reduction gears to provide increased ground clearance. The propulsion unit in the water was a primitive application of the inboard/outboard system. In this case, the three-bladed prop was on the end of a jointed arm that was stored vertically in the ‘up’ position when the car was on land.

When you hit the water, you manually swung the prop arm down into place by way of an over-centre device and engaged the propeller, which was connected via a dog clutch directly to the engine crankshaft. Unfortunately, unlike a real boat, there was no reverse gear and no rudder; the 16 x 6 in. front tyres served that purpose. Canoe paddles and long poles were also provided in case the motor cut out in mid-stream. A top speed of 80km/h was possible on land, and 10km/h in water. Fuel was carried in two front-mounted petrol tanks, containing 24 and 26 litres of fuel.

Two other Porsche products of interest that utilised the 25-PS Volkswagen engine were the Type 164 project, a six-wheeler powered by two Beetle engines, though it was never developed beyond the prototype stage. The other project was the massive Porsche Type 205 Maus (mouse), a 185-tonne mobile fortress tank which used a Beetle engine to activate its auxiliaries. Only two of these were ever completed. One was destroyed by the Germans before the war ended, while the other was captured by the Russians and today is in storage at the Kubinka Tank Museum in Moscow.

Today Schwimmwagens are very rare. Only 14,283 had been made at Wolfsburg, and by Porsche at Stuttgart, when production ceased. Besides large losses of the vehicles in combat (they were mostly used by the elite SS on the Russian front), under the terms of the peace treaty the Schwimmwagens were classified as Naval vessels, and had to be cut up for scrap. Today there are about 130 of them in museums and in the hands of collectors around the world.

Wolfsburg 1945-1946 1

By Greg Figgis

April 1987

May 1945 and Nazi Germany has surrendered. The first Allied units in the Wolfsburg area were American, but the town lay within the British Zone of Occupation. Therefore a British Army detachment consisting of the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (REME) and Rear Area Operations Centre (RAOC) took over the VW works shortly afterwards.

The first post-war activity at the factory was the repair of captured enemy vehicles for German essential services, under the direction of the REME.

Under the REME’s control, what remained of the VW works also arranged the assembly of Jeep-type Kübelwagen VWs from existing parts, but the limiting factor was the availability of body shells that had previously come from the Ambi-Budd body plant in Berlin, now in the Russian sector.

One of the few remaining Beetles that had been built at the beginning of the war was sprayed khaki green and driven to British Army headquarters as a demonstration model. The result was an order for a batch of Beetles.

However there were quite a few problems before production could commence. There was extensive damage caused by Allied bombing. In the severe winter of 1945-46 the roofs of many of the giant buildings were open to the sky.

Giant girders lay twisted on the ground and valuable machinery lay about damaged. Official war records show that the RAF in 8 major raids had dropped a total of 206 high explosive bombs on the factory. The first raid was in 1940, but the biggest raid was on 20 June 1944 when 90 RAF bombers and 30 fighters took part.

Structural damage to the Wolfsburg factory due to air raids amounted to a total of 105,000m2. As a result of the raids, 60% of the production area was destroyed.

Also there was insufficient electrical power due to a lack of coal for the factory’s huge power station; a major shortage of serviceable presses, dies and machine tools, and a shortage of vital components – sheet metal, tyres and ball races. There was a distressing lack of food for the initial 450 workers, and in the background was the uneasy presence of a Russian unit comprising 2 officers and 30 men who were encamped in the village, eager for war reparations and with high hopes of salvaging undamaged machinery for ultimate use in Russia.

Perhaps the most serious problem was whether the Allied Control Commission could justify the existence of the Volkswagenwerk.

The British officer in charge of the factory was summoned to urgent talks with his regional chief in February 1946. He was told that with other Allied countries, especially Russia, clamouring for serviceable machinery for reparations, there would have to be practical proof that the Volkswagenwerk was still an essential and productive factory, otherwise it would have to be dismantled. The required proof for the factory’s continued existence would be the turnout of 1,000 new cars a month by the end of March.

The first step towards production was calling the German heads of the various Volkswagenwerk departments – about 35 supervisors in all – to a meeting. About 10 of the Germans had worked in American car factories before the war. The facts were told to them and they agreed to give it a go, so long as food and blankets were made available.

To get the factory back into production, working parties were organised to cut down the tangled girders, repair the wide-open roofs and remove the acres of rubble. To replenish Wolfsburg’s empty coal bins, the official in charge of a railway detachment at a nearby mainland junction was ‘bribed’ with a new Volkswagen Beetle, with the result that a trainload of coal on its way to Berlin was ‘hijacked’ to Wolfsburg!

The power station slowly returned to action, pumping steam, heat and electrical power into the gradually revitalised factory.

Red tape was cut to shreds. The reduction gears of two British automatic machines used for machining the crankcase were found to be broken or lost. A letter was sent to the chief of the British engineering firm who had made the machines, begging him to send the replacement gears with the upmost speed. The managing director of the firm actually flew to Germany with the gears!

Most of the precision machinery had escaped damage because it had been stored in separate compartments in the basement. Some had also been stored in a disused mine in the Harz mountains, where they had been placed for safekeeping towards the end of the war. Other precision machinery was lost when it was quickly claimed by Peugeot of France as their property.

The engine assembly shop was also located in the basement and was partly flooded, so duckboards were laid down for the workers.

Tyres and ball races were begged and borrowed from factories all over Germany. Tyres were so scarce that at one time during that all-important month of March 1946, there were hundreds of half-completed VWs on the factory floor on wheels minus tyres!

A temporary body assembly line was installed in the press shop, and jigs and fixtures were made to replace those damaged beyond repair.

Another difficulty was uneven ductility of sheet metal, due to the lack of instrumentation for the annealing furnaces at the rolling mills. Local annealing with an oxy-acetylene flame between drawing operations was the answer.

Improvisation was the order of the day. No fewer than 600 bodies were made with the roof in three thicknesses of steel. This was made possible by digging out from the wreckage of the factory and getting into working order again a complicated machine which butt-welded three sheets of steel together.

It didn’t do the dies any good but they only had one master jig for body manufacture.

All the engine machining was done in the factory except for the pistons and rings and cylinder barrels. The gearbox was also machined on the spot, as was the ring gear pinion and star pinions, and also the front axle.

The general standard of cars produced at this time was pretty low. The paint finish was rough and the doors a bad fit, but mechanically they were quite good. Three engineers from Ford of Great Britain visited the factory to test the VW, and tried to run one into the ground but failed. All they could manage was to make the doors fly open on a rough road.

It is interesting to note at this time that the officials in charge had a couple of Schwimmwagens made up at the factory from left-over parts, to use for duck-shooting. I wonder whatever happened to them?

Another critical problem was the carburettor, which had been made in Berlin under Solex licence. There was no manufacturer anywhere else in Germany, so the small parts were taken to Voigtländer, the camera makers, while the body and float were made at Wolfsburg.

Trouble arose when an Allied officer was killed driving a Beetle which crashed for no apparent reason. This was a crisis, especially when several other officers were involved in similar mysterious crashes. Volkswagen’s revolutionary steering and front suspension were suspected of being unsafe.

The Allied Control Commission began to take an official interest in the matter, and the outlook for the Volkswagenwerk began to look grim just as production was getting into full swing. A ‘stop production’ order from HQ was given, pending the arrival of an investigation team from England. Tests on the steering arm proved one thing – they were tough. The destruction tests that were applied failed to break up any of the steering arms selected. Otto Hohne, then the production chief, went one step further and disconnected one steering arm from a test Beetle without telling the investigation team. After taking them for a test run, he showed them what had been done, much to their amazement!

The VW, because of its trailing arm type of front suspension where the wheels are pulled, rather pushed forward as with more orthodox cars, could actually be driven with one steering arm disconnected! The reputation of the Volkswagen had been cleared, the factory was given official permission to continue production, and the accidents were put down to driver error.

Did the Volkswagen achieve the 1,000 cars a month deadline? By the end of March 1946, 1,003 Volkswagens had rolled off the production line!

Sizeable orders were received from the US Army and the French Army, and cars were also supplied to German essential services. In all, some 20,000 cars were delivered under these headings. Output from other German car factories in this period – BMW, Opel, Ford and Daimler-Benz – was virtually zero.

Wolfsburg 1945-1946 2

By Greg Figgis

September 1987

The Americans were the first into Wolfsburg, followed by the British who set up a REME workshop in the ruins of the Volkswagenwerk and who then, as mentioned in the previous Wolfsburg story, got production going again.

However, much to the concern of the Germans and the British, a Russian Army detachment arrived and set up camp in the middle of the village. The Russians left no doubt in anyone’s mind that this was a Red Army outpost. The Russian camp could be spotted a long way off by its dominant feature – they had erected a large hardboard framework about 10 metres high, covered with giant pictures of Stalin! This propaganda spectacle was floodlit at night, but when the coal supply was low at the power station the electricity was cut off, which didn’t please the Russian major at all!

The Russians gave no trouble at all. Much drinking was done when two Russian officers arrived at Wolfsburg to collect the first 50 VWs exported from the Volkswagenwerk after the war. How close Wolfsburg came to being located in the Russian zone can be judged from the fact that at the end of the fighting the Red Army had penetrated as far west as Hannover (60km WEST of Wolfsburg), and when the line of demarcation was finally fixed these Red Army forward units reluctantly went back to the East as far as the next village east of Wolfsburg.

The Allied Control Commission officers themselves were inclined to be jumpy about what the Russians’ next move might be. From time to time the political situation flared up with the Russians, and none of the British officers wanted to be overrun and taken prisoner, so they kept their VW staff cars fully gassed up and under floodlights outside their quarters for a possible quick getaway.

German executives at the Volkswagenwerk were very conscious of the Russians’ unconcealed interest in the valuable precision machinery housed undamaged in the basement of the factory. Some of it was highly specialised equipment that had been used during the war in the manufacture of components of Junkers Ju88 aircraft and for the V1 and V2 rockets (which was why the Allies had bombed the VW factory). But did the Russians have any technical knowledge of the Volkswagen car or of the valuable machinery housed in the factory? No, definitely not. The Russian contingent that arrived to collect those first 50 export VWs had to be taught how to drive them!

Any public disturbances during 1945/46 were caused by Polish refugees and former POWs, who lived in a controlled camp in the village. Wolfsburg was a collecting point for thousands of homeless Polish families, who were kept in the transit camp under official supervision for one or two weeks, before being sent back to Poland via East Germany aboard special trains. The trouble the local Germans had with the Poles was tremendous; they were always on the rampage.

More trouble surfaced when the French took delivery of their first consignment of Volkswagens. The cars were loaded onto flat carriages and the train was ready to pull out that afternoon, but in some strange way the steam engine failed to function. The train didn’t leave until dark. Then, when the train stopped at the end of the spur line to get onto the main line, it was invaded by local Germans who knocked off wheels and various other parts. By the time the train reached Baden Baden quite a lot of the parts were missing. When the next train-load of Volkswagens left for Baden Baden, there were a large number of gendarmes riding shotgun on the rail cars.

The French were keen to find stolen French equipment, and called at the Volkswagenwerk to inspect a butt welder to check and see if it had been made in France. The butt welder, however, had in fact been made at the Volkswagewerke’s tool shop outside Braunschweig, where all the special tools for the factory had been made. The French were wined, dined and entertained at the factory by the British, but they got nothing. Speaking of stolen equipment, a lot of thieving went on around Wolfsburg and the factory. Stocks of a new batch of upholstery material were steadily dwindling for no apparent reason.

Then someone noticed that some of the women workers appeared to be putting on weight. When they were searched it was found that several of the women had wound the material around their bodies to get it out of the plant. A lot of wheels and tyres went missing also.

Some of the Germans could strip a car of its wheels and tyres in a few minutes. After they had removed the wheels, complete with tyres, they threw them into the canal alongside the factory. The weight of the wheels would sink the tyres to just below the surface of the water, and then after dark they would be retrieved by boat.

When the situation got really bad, special British security forces were called in, who discovered that one of the factory police chiefs was in league with the thieves.

When there was a stoppage in production, in any department, for any reason, telephone calls would get a five-man trouble-shooting team on the spot within minutes to sort out what was going on.

Much of the trouble was due to poor inspection of various machine jobs, and a number of machines were in need of overhaul.

Up to this time there was only one master body jig, but another was being made up. Later the Americans came along with offers of Lend Lease, and eventually all the gear-cutting machines were replaced with new ones from Cleveland, Ohio.

Finance to get the Volkswagenwerk back onto its feet was arranged through the Finance division of the military government with the Deutsche Bank for an overdraft on behalf of the Volkswagenwerk for the equivalent of a quarter of a million pounds. How was the amount of money needed to get the factory back on its feet calculated? It was purely an arbitrary figure, and it was based on a reconnaissance and estimate by the British who were in charge of the plant at the time. In fact, the loan was just a credit with no collateral security apart from the works itself.

The next instalment of Wolfsburg 1945-46 will feature the first VW Cabriolet and the change from British to German control, and the Australian connection.

Wolfsburg 1946-1949

By Greg Figgis

February 1988

Two interesting experiments carried out at the Volkswagenwerk in 1946 were the adaption of twin carburettors to the VW engine, and the development of the Cabriolet. Three Volkswagens were fitted with twin carburettors, but it was not much of a success. It was difficult to get good idling characteristics with the standard flywheel, which was too light, and fuel consumption increased dramatically, although top speed was increased by about 15km/h.

The modifications were a bit crude and made up from bits and pieces, which I suppose was to be expected, considering that the factory was in shambles.

A successful experiment carried out in 1946 was the Cabriolet. Two firms were given the chance to make a Cabriolet version of the Volkswagen: Karmann of Osnabrück, and Hebmüller of Cologne. Each company was given a body shell to cut down. When the prototype bodies had been prepared and road tested, however, it was found that by cutting the roof from the body the rigidity of the whole car was affected. The side-members of the body had to be strengthened, as well as the front door pillars and windscreen frame. After some further detail changes, it was decided to finish a few and an order for 100 was given to Karmann by Julius Paulsen, the works purchasing manager.

Until now the factory had been operated solely for the Forces of Occupation, but the original plan whereby Germany was to have little industry had been dropped, and more thought was being given to the country’s economic viability.

The Allied Control Commission consequently found itself taking an increasing interest in the possibility of exports from German manufacturers.

Officially the Allies were expected to do all they could to improve Western Germany’s economic situation, in order to ensure a reasonable standard of living in the Allied sectors as a bulwark against Communism. This was the time of the Iron Curtain and the Berlin Airlift.

Volkswagen was steadily gaining momentum. First and foremost was the question of the management. The original post-war Plant Manager had fallen a victim to denazification, as had an excellent Works Manager appointed from outside the firm. The original Purchasing Manager had been elevated to Supplies Manager. The sales and service managers were performing well.

In short, the team was taking shape, but the right man still had to be found for the top appointment.

An assured future allowed for authorisation of more expenditure on building reconstruction and the replacement of machines and new plant to fill the gaps.

Elsewhere in Germany too, the position was improving and supplies were becoming easier. The total workforce at Wolfsburg was now approaching 10,000. Thus it was possible to step up production, and alongside deliveries for occupation requirements, cars now began to flow into the German economy. An export department was opened and Holland was the first country to which VWs were exported.

During 1947 Heinz Nordhoff was recommended for the top post of General Manager. This recommendation was confirmed and fully endorsed in January 1948. From then onwards, the Allies withdrew into the background.

Heinz Nordhoff continued to be responsible to the British board, but it was no longer necessary for the British to take direct action on day-to-day matters. The Type 2 Transporter project was put in hand, and building work continued at greater speed. It was then possible to improve the plant layout, especially for body assembly. Throughout, the commercial affairs had been managed on sound lines, so there were funds available for ploughing back into plant equipment.

In the autumn of 1949 the chairman of the British Control Board met the new Federal Minister of Economics and handed over the Volkswagenwerk, which has since been organised as an AG (Aktiengesellschaft) with part of its capital belonging to the private sector.

An interesting side play in 1948 was the Australian government’s interest in the Volkswagen factory. The Labor government of the time wanted a lower-priced ‘people’s car’ than the Holden for the Australian people. Lloyd Hartnett of Holden fame was instructed by the Government to look into the viability of the VW and other European cars.

The Renault 750 was considered, but Renault insisted that no change be made to their product for Australian conditions. FIAT was also approached, but the same approach as for Renault was insisted upon. Hartnett wouldn’t recommend an arrangement with such conditions, so the Renault and FIAT plans were dropped.

The Australian government believed the VW to be very cheap to produce because at that time surplus production cars were being sold for whatever Volkswagen could get for them. Sold under these conditions it WAS a cheap car, but nobody at the Volkswagenwerk was doing any costings, and currency values in Europe hadn’t yet settled down.

The Australian government was planning to move the VW works down under and set them up in a wartime aircraft factory in Victoria. However there was no proof that the VW would have had public acceptance in Australia, and eventually the plan fell through. It is believed that another motor vehicle manufacturer ‘persuaded’ the government to let them in and set up a factory. As it turned out, a well-known British manufacturer took over the aircraft factory.

As it was, Australia, with its British heritage, connections and family ties, got dumped with lots of pre-war English ‘rubbish’.

We VW lovers had to wait another five or six years before we got a car that proved itself over and over again to be utterly reliable and robust under the demanding Australian conditions of the time.

The Evolution of the VW Symbol

By Ray Black

February 1989

The story begins with the ‘Arbeitsfront’ (Workers' Front) symbol. This symbol was used on all national works programmes, which included the ‘People’s Car’. The foundation stone at the Wolfsburg factory incorporated this symbol. The People’s Car was designed to be part of the KdF movement: a national recreation plan embracing hiking, mountain climbing, camping, etc. KdF stands for "Kraft durch Freude", which means "Strength through Joy". The "Volkswagen" (People's Car) was only a working name at this stage as the ‘KdF-Wagen’ was to be its official name.

This variation was used on certain items in the early days of the KdF-Wagen. Note the spinning swastika. This may be the origin of the belief that the current VW symbol, rotating at a certain speed, transforms into a swastika.

Many people connected with the design of what is now the VW, did not like Hitler’s idea of naming it ‘KdF-Wagen’. The name ‘Volkswagen’ was much preferred by Dr. Porsche, and, as a result, one of Dr. Porsche's engine designers, Franz Reimspiess, designed a ‘VW’ for the centre of the cogwheel device. He was rewarded with a bonus of 100 Reichsmarks. This ‘VW’ within the cogwheel, surrounded by the spinning swastika, was accepted as the new symbol and heralded in the still unofficial new name Volkswagen.

Possibly because of the need to cast and stamp the symbol into all car components, the complex spinning swastika background was dropped, and so the simpler VW within the cog was born. This, ironically, is still referred to today as the KdF logo and determines genuine wartime-manufactured vehicles and parts.

After the war, as part of the de-nazification programme, the cog teeth were removed, because of the strong political associations. The now-famous and classic VW symbol was created and remains, with various aesthetic changes, to this day.

Ferdinand Porsche – Versatile Genius

Adapted by Ray Black

February 1989

One day during the First World War the British car manufacturer Henry Royce, creator of the worlds first limousine, was listening to his engineers argue about engine output when he decided to end the discussion. “Gentlemen!” he said, “all I know is that this is the performance Porsche of Austria has achieved. Therefore, it must be the best possible!”

In that tribute was summed up the secret of Ferdinand Porsche’s automotive genius. A perfectionist who drove himself and his assistants hard, he was never satisfied with the run-of-the-mill or second best. Though he designed several extraordinarily sophisticated engines, he kept searching for the simplest and most rational key to complex technical problems.

Porsche, a self-made and largely self-educated man, was an inspired tinkerer who ranged all over the automotive map, designing vehicles of a fantastic variety of shapes and types. And though he catered to the rich for most of his life, his most stubborn dream was to produce a modest, robust car that the average man could afford. The result was the Volkswagen, one of the sturdiest and most successful cars ever designed.

Few men in history have dedicated themselves with a more concentrated single-mindedness to their profession. Ferdinand Porsche had no hobbies to speak of, was totally uninterested in politics, and preferred work to exercise He was always in his office by 7 am, often studying a sketch he had modified after his designers had gone home the night before, impatient now to discuss it with them. Hours of tense talk would follow, for once in the grip of a new idea there was no getting him away from the drawing boards. One of his associates recalled, “in those days I was always hungry for lunch.”

In temperament he had the tenacity of a terrier. Though short and unassumingly dressed in a felt hat and tweeds, he could be singularly imperious if he chose. His wrinkled smile would freeze, his trim toothbrush moustache bristle aggressively, his hazel eyes grow hard as flints. With his closest associates in particular he could be demanding to the point of exasperation. In New York he once ordered his private secretary to get him tickets on the Queen Mary, though he didn't have one American cent to pay for them. When the resourceful secretary returned to say that the shipping company would get around the regulations and accept German Marks, and that he had been given the finest stateroom on the ship, he merely nodded gruffly.

Yet even his severest critics had to admit he was a genius. The range of his inventiveness was prodigious, stretching from an electric-powered carriage he built in 1900 to a monstrous 180-tonne tank he designed during World War II.

He was the first to equip a car with brakes on all four wheels and the first to design a mixed electric-drive, petrol-powered vehicle. Above all, he developed the ingenious torsion system of suspension that was used for decades on Volkswagen and Porsche cars.

Some inventions that looked at first like crazy cartoon creations were in reality decades ahead of their time. Shortly before World War I he came up with a mixed-drive tractor capable of pulling two ten-tonne trailers. But while an ordinary tractor would have been stalled by the 20 tonnes it had to move, Porsche’s model moved at a steady 18 km/h because each trailer’s wheels were driven by electric motors powered by a cable from the tractor’s generator. The same principle today propels much earth-moving equipment.

Twenty years later Porsche again surprised the world by fitting a 16-cylinder engine into a racing car behind, rather than in front of the driver. "The man's crazy!" was the general reaction when Auto Union's ‘Silver Arrow’ first made its appearance. But in 1934 alone it broke seven world records. Later models, souped up to 545 horsepower, won race after race in a breathless duel with Mercedes which for six consecutive years - 1934 to 1939 - swept Bugatti, Alfa Romeo and Maserati from the field.

The internal combustion engine was little more than an idea in 1875, when Ferdinand Porsche was born in the Austrian town of Maffersdorf (now part of Czechoslovakia). In fact, there was good reason to believe that ‘horseless carriages’ would be powered by electricity or steam. The son of a modest tinker, young Ferdinand believed that electricity was the key to the future, and spent much of his spare time in the attic concocting home-made batteries out of jam jars and sulphuric acid. At a nearby trade school he learnt the rudiments of technical drawing and geometry, and soon knew enough to be able to make generators as well. One day, when his father was called away to a neighbouring village, he rigged up a flywheel-operated dynamo, a voltmeter switchboard and an entire electrical circuit. When his father returned, he was amazed to find his house aglow with electric bulbs!

Impressed, the tinker agreed to send his son to Vienna for further training. Four years later the 22-year-old Ferdinand was already running the Bela Egger Electric Company’s testing department.

Word of his inventive talent soon reached the ears of Ludwig Lohner, carriage-maker to the Hapsburg court, who asked him to help build an electrically powered carriage. The result: a compact four-seater that caused a sensation at the 1900 Universal Exhibition in Paris. Its front-wheel hubs contained two 23-hp electric motors that could propel the carriage at up to 60 km/h, and for the first time in history all four wheels had brakes.

In 1923 a dispute with the chairman of Austro-Daimler in Vienna ended Porsche's 17-year career with that company, and he moved his wife Aloisia and their two children. Louise and Ferry, to Stuttgart, where he became technical director of the German Daimler works. Never happier than when he had a spanner in his hand, Porsche had trouble gaining acceptance among the factory's stuffy executives and engineers, who expected him to sit at his desk and review designs brought to him for examination. But this was not Porsche's way of doing things. One day, when he found the white-clad engineers standing around a defective model arguing over the possible causes of the trouble, Porsche picked up a screwdriver and a spanner and crawled underneath the car. When he finally emerged, a bystander was rash enough to ask what he had found. “Go and look for yourself, you blockhead!” he rasped and stamped away. Porsche was not an armchair manager, and he was not going to be served by armchair engineers.

In 1930 he decided to strike out on his own by founding a design studio to develop new car engines and ideas for other firms. Consisting of ten close associates, the Porsche Construction Bureau was at first a shoestring operation. Its quarters were cramped, and to make ends meet Porsche had to borrow against his life assurance policy. Salary payments were erratic. Yet out of these modest facilities came a number of epoch-making blueprints.

One of the first was a revolutionary version of the torsion-bar suspension system, which Porsche and his chief designer, Karl Rabe, developed to replace the heavy multiple-leaf or coil-spring suspension of earlier cars. It was successfully sold to Morris, Citroen, Standard, Volvo, Alfa Romeo and other firms. “If Porsche had never developed anything else but this torsion bar,” German car expert Hans Brelz once wrote, “his name would still have acquired immortality as an inventor and constructor.”

No less original were the plans that Porsche drew up for a future People's Car. To begin with, its engine was air-cooled. Next, it was so far behind the driver that it protruded beyond the rear axle. The four air-cooled cylinders were paired off horizontally, yet again a radical departure from the usual layout and an anticipation of the basic pattern which Porsche cars have followed ever since.

Finding a sponsor to mass-produce this car proved far more difficult than designing it, but when Hitler became Chancellor in January 1933 Porsche saw an opportunity in the Fuhrer’s earlier campaign promise to help the German car industry. He obtained an audience with Hitler and a few months later submitted a memo on the future Volkswagen.

Most German manufacturers were hostile to the small-car idea, however, and tried their best to abort the project. Porsche and his associates went ahead anyway. Parts were ordered from various firms and assembled in the only place Porsche could find - his own garage, which he enlarged and converted into a workshop. By 1935 the first prototypes were ready for testing and the problems of mass production loomed. The official target was 15 million Volkswagens, but no factory in Europe was then capable of rolling so many cars off its assembly lines. To see how American manufacturers coped with such problems, Porsche made two trips to the United States. Meanwhile, a pre-production series of thirty Volkswagens were test-driven over mountain roads for a collective total of more than two million kilometres - the most exhaustive testing to which any car in Europe had yet been subjected. As a result, the green light was given and construction of a plant near the village of Fallersleben commenced in May 1938.

By the time the factory was completed in October 1939. World War II had begun and the plant soon started production for military needs. Later on, Porsche was appointed chairman of the Ministry of War Production's Panzer Commission. Inventive as ever, he adapted the Volkswagen to military needs, producing the Kübelwagen, a jeep-like scout car whose air-cooled motor proved invaluable in the Russian steppes and in the North African desert. An even more ingenious adaptation was the Schwimmwagen, equipped with a propeller; more than 17 000 of these cross-country amphibious vehicles were built during the war. Meanwhile, Porsche's little Construction Bureau in Stuttgart blossomed into a thriving business with its own factory.

Porsche's fascination with technical problems blinded him to the political consequences of his involvement with the Nazi regime, a mistake that was to cost him dearly. Some of the projects he worked on used forced labour, an onus that remained with him to the end and embittered his waning years. After Germany's collapse, he was arrested first by the Americans, who released him after a few months, then by the French, who imprisoned him under unfounded charges for almost two years. His Stuttgart factory was taken over by the occupation authorities, and when he was finally released in 1947, he was a broken man.

Yet the sheer force of Ferdinand Porsche’s inventiveness and achievement carried him throughout this sombre period, and shortly after his release he was hard at work on an eight-cylinder sports car that was the forerunner of today’s sleek road-hugging Porsches. A revived Volkswagen company had been in production since 1945, paying him a royalty on every car produced, and over the next few years the initial trickle of money gradually swelled. Further recognition came in 1950 in Stuttgart, where his 75th birthday was celebrated with the first Porsche car rally ever held. Four months later, he died peacefully.

His achievements, however, remain very much with us. The Stuttgart factory, which was returned to the family in 1952, has grown from a few workshop sheds to a modern plant that has turned out hundreds of thousands of prestigious sports cars. On the world's racing circuits, high-powered versions of those speedsters are among the most consistent winners. And in all corners of the earth, the clatter of the Beetle proclaims the enduring brilliance of its creator. Around 21 million have rolled off the assembly lines in more than a quarter-century of unbroken output – along with that of the Citroen 2CV, one of the two longest runs of any car in history.

Like its creator, the VW was a product homely and visionary, simple and sophisticated.

The Denzel Sports Car

By Dave Long

May 1989

This is on the subject of the Denzel sports car, and the man who built them, Wolfgang Denzel. Denzel was a motor sport enthusiast who began modifying 1100cc VW engines for competition almost 40 years ago.

One of his earliest attempts at a competition car was derived from a Kübelwagen, and with streamlined body and improved running gear, it served as a prototype for the eventual Denzel 1300 sports car.

Probably the most outstanding aspect of this saga is that when Denzel was occupied in Vienna, not far away at Gmünd, also in Austria, Ferdinand Porsche was engaged in activities of his own, along similar lines. At that time, in the middle 1940s, both were working independently to develop a small, rear-engined sports car. Common to the two constructors was that both chose the early Volkswagen engine as the basis for their designs. To be fair to Porsche, he had been responsible to a large degree for the creation of the Volkswagen engine.

Material shortages immediately following the war made their operations difficult, as the limited production relied on a supply of VW components; ‘production’ components initially were scrounged from some very second-hand sources, usually war surplus. Even at the infant Porsche works at that time conditions were tough; Dr. Ferdinand had been virtually ransomed from prison where the French had interned him since the war. Three cars were initially built, including the narrow coupe which has become known as the ‘Progenitor Porsche’. Before production could continue, these had to be sold to raise capital for more cars.

Contrasting Denzel and Porsche, however, it is remarkable that the approach of the two manufacturers, while so diverse, should see them reach such similar results.

Very few know of the achievements of Denzel; everyone knows of Porsche. Wolfgang Denzel is descended from a line of bell founders, whose history goes back more than 400 years. This founding tradition probably stood him in good stead for aspects of his small-production sports car manufacturing. At first engines were a direct adaptation of the 1100cc unit we know as the 25 hp - the Germans probably knew it as the 20 PS. This power unit was modified to give 38 hp SAE, an increase of more than 50%. In a car only weighing 590 kg, it posted a number of competition successes from 1949 to 1952.

In 1952, in place of the VW floorpan, a tubular frame was designed and integrated with a sleek aluminium body. This car weighed just 545 kg, and was 3505 mm long, with a short wheelbase of about 2080 mm. It had relatively large wheels, alloy brake drums, and was designed with a minimum overhang at each end, in keeping with its sporting character. This feature allowed sharp entry and departure angles on tight mountain roads.

It had a new engine, still VW-based, of 1290cc, employing the 64 mm crank with 80 mm cylinders. Compression was 7.5:1 and power output reached 52 hp SAE at 4400 rpm.

There was also a more sporting version measuring 74 mm x 74 mm whose compression, while high, was not disclosed. Power was 64 hp SAE at 5400 rpm. These engines both employed cylinder heads of special Denzel design, as well as chromed aluminium cylinders, but were based on the stock VW crankcase.

While Dr. Porsche and Mr. Denzel had similar objectives, to produce a light, agile sporting car, their purpose was quite different. Porsche was involved in small production specialist car manufacture, whereas Denzel developed his car because of a keen and active interest in motor sport. He had conceived the idea prior to 1947 to furnish himself with a competitive vehicle to contest the 1300cc class of the Alpine rallies and trials, which at the time were so prevalent around the Alps of his native Austria and surrounding areas. Having enjoyed outstanding success, including many class victories and an outright win in the 1954 International Alpine Rally (an occasion where Stirling Moss managed only 10th!), the cars proved so effective that they were built and marketed in small numbers, allowing others their ‘moment of glory’ whether competing or simply touring. In 1949 a Denzel had taken the Austrian Alpine Rally, and did it again in 1952, with less than 1100cc and 38 hp! The newer 1300cc car carried off the 1500cc sports car class of this event in 1953.

Denzel sports car production continued for 10 years until 1959, in which period a total of approximately 350 cars were made. In addition the small Denzel works produced separate engine kits for the 36 hp VW engine block, and rumour had it there were similar components available for a while in the 1960s to suit 40 hp types, although I have never confirmed this.

KdF-Wagen Sparkarte

By Rod Young

October 1989

The KdF-Wagen Savings Certificate shown below was found by Geoff McVey, but I’d like to make a few comments on it.

The owner of that particular piece of paper was no ordinary good German worker. Ghislaine Kaes, whose occupation is given as ‘Sekretar’, was only Dr. Ferdinand Porsche's private secretary!

I wonder when/if Mr Kaes finally got his Beetle, since none of the citizens who conscientiously saved up their five Reichsmarks per week actually ever received a KdF-Wagen, what with a well-known military action intervening in the meantime. In the early 1960s legal action was instituted against the Volkswagenwerk for delivery of cars for which money had been paid. VW, though in no way connected with the pre-war KdF organisation, obliged by giving holders of a ‘Sparkarte’ a discount of up to 600 DM on a new Beetle, or a 100 DM cash grant.

It has been claimed by some commentators that Hitler's plans to motorise the German public had been a swindle, that the factory was built for military purposes and the money that had been collected from faithful savers, altogether 267,867,937.30 Reichsmarks, was put to use in the war effort. In fact, to my knowledge, the funds collected under the savings card scheme remained intact in a Berlin bank vault until the end of the war, when the victorious Russian Red Army confiscated them. It appears that this was one promise that Hitler planned to make good.

Mr Kaes’ card has some interesting details. The expected year of delivery (voraussichtliches Lieferjahr) is not indicated. His place of residence is shown as Stuttgart - of course, this is where Porsche had his design bureau and is still the site of the Porsche works. He possessed a class IIIb driver's license, noteworthy because possession of a driver's license was by no means common at the time.

During the Hitler years, Germany was divided into ‘Gau’, or districts. At the place on the certificate indicating the ‘Gau’ of issue of the card, ‘Volkswagenwerk’ is entered, since the name ‘Wolfsburg’ was a post-war coining, and the name of the gestating town was an unwieldy ‘Stadt des KdF-Wagens’ - City of the KdF Car.

The ‘Volkswagenwerk’ stamp also contains the letters ‘G.m.b.H.’, which means more or less ‘Pty. Ltd.’ This suggests a private company, though as we know, the works was controlled by the K.d.F front, a state-run organisation. A bit of a mystery to me.

Mr. Kaes had been sticking down his weekly 5-Mark stamps ever since August 1938. Fifty of these in a year made up the 250 Mark entries in the left column. He didn't have far to go to make up the 990 Marks.

There is a notice stating that if you lost your card, it could not be replaced, meaning that the prospective owner would have lost all. They wouldn't have been left lying around in that case.

There is a section at the top of the left of the card for additional stamps to cover special equipment (I wonder what trendy accessories you could get?) and transport costs. Mr. Kaes wasn't into accessories - he was to get a ‘Limousine’, or steel-roofed, standard (grey)-coloured KdF-Wagen.

Savers could spare themselves transport costs by taking delivery of their car at the factory. Hence an entry for place of delivery, which is given as ‘Gaustadt’, or Stuttgart in Mr. Kaes' case. However, he is not charged for transport costs – he must have known someone in the business!

Insurance was a relatively hefty 200 Marks, one fifth of the car's value! However, the length of insurance cover is not stated.

Flashback – Gene Berg

By Dave Long

February 1990

I hope you're not all tired of reading about Gene Berg and his exploits, because I came across more information that puts the old engine hot-up article more in perspective. This is from DB&HVWs as it was then, and started life as an interview by Jere Aldaheff. I intend to turn it into a straight narrative, so see what you think.

“The way I started with Volkswagens was that I couldn't get it fixed, so I ended up always doing it myself. The first thing you know, I had neighbours' cars to fix. In 1960 I went to work for the VW dealer in Kenton, Washington, and worked there for two years. I took the position of service writer with the stipulation that I would attend the VW train¬ing schools. Part of the time I wrote service but I also learned all the facets of the business from lube jobs to engine work. At this time I also attended the VW mechanics and service writers training school. This was from October i960 to August 1962. I left there and began painting cars at home and doing furniture upholstery. Pretty soon the Volkswagen customers began to find me.

“About a year later, Enco built a gas station 200ft from my house, and I leased it and worked on Volkswagens there. A year later Enco decided that working on VWs and pumping gas didn't mix. I said I was going to work on cars, so I left. I bought some property behind my house and built a small garage there. I worked in that shop until I moved to California in 1969.

“In 1961 after I started at the VW dealer, I met a guy named Lonny who had a Porsche-engined VW sedan. He decided he wanted to build an X-dragster (4-cylinder class) with a Porsche engine. Every time the car would run close to the record, a Model-A Ford dragster in California would lower it. Lonny wanted to sell the dragster, and I bought it complete with Porsche engine. I put a Corvair engine into the dragster for a while, then I put toge¬ther a VW engine for it. I had gotten to know Dean Lowry pretty well by this time. The dragster benefited immediately from the engine - the first run was in the mid-11s. They changed the rules and allowed 6-cylinder and Straight-8 Buick engines in the class. A dragster with dual Straight-8 Buicks lowered the record into the 10.70s. So I pulled out.

“To give an idea how involved was this first drag racing effort, we had a '61 VW sedan with Porsche engine. We would carry the dragster less engine on a roof rack on the sedan. When we arrived at the track, we would remove the engine from the sedan, change the exhaust, remove the engine tin, install it in the dragster and go racing. We would run X class with the dragster, then put the engine back in the sedan for H/Gas class. If we won H/G we'd run Street Eliminator with the sedan, then put the engine back into the dragster for Little Eliminator. After Little Eliminator we'd win four trophies in one day with the same engine in the two cars. We never even thought of breaking the car, never even dream¬ed about it.

“I sold the dragster less engine in 1964. I installed that engine in my 1964 VW sedan and with stock gears in the transaxle and 155 Pirelli radials on the rear, we smoked the tyres and ran a 13.00 going across the finish line in third gear. I never even dreamed the engine would run that time in a sedan. When that engine was in my dragster, Dean Lowry held the H/G record at 14.30 and that was using a Porsche close-ratio gearbox. Both our engines were the same size, too. It was a 74mm Okrasa stroker with 90mm Corvair pistons and cylinders. The heads were Okrasa (twin port) with 36HP VW rods. It had Pontiac valves in the head (40 inlet by 34 exhaust). I made the inlet manifolds since Okrasa did not make manifolds to fit the Solex 40-P11 carburettor.

“In 1966 we switched to the new VW dual port heads and bought EMPI manifolds which promptly broke, so we made castings ourselves. Actually, this was the beginning of our manufacturing. We couldn't get quite the product we wanted. At that time there was a lot of difficulty with parts breaking or not fitting. We figured we could do as well or better.

“We started with intake manifolds, then an oil sump like EMPI’s, only ours could be removed with a socket rather than an open-end wrench. I couldn't afford a Porsche transaxle so I decided to make close-ratio gears for a VW. The first ones were horrible. We only intended for them to get us down the ¼-mile. It didn't matter if they were noisy or if they wore out. They were built for our use, not for resale. Eventually the quality increased, and the gears are now very good. We sell an awful lot of gears now, in many various ratios.

“A while after that I moved to California, and it happened like this. In 1960 Dean Lowry left EMPI and along with his brother Ken began Deano Dyno Soars. I was making their intake manifolds, linkages, sumps and close-ratio gears. We'd made some ratio rocker arms by then, out of Porsche rocker arms. After coming down for the early Bug-Ins and the SEMA show, we moved in June of 1969 and I bought into Deano's and began working there. After six months a communication problem with Ken caused me to leave, and I moved my stuff out into the street. I was flat broke but Dave Vanderbecke let me share his shop for one month, then I found my own building and opened shop on 15th Dec¬ember 1969, manufacturing parts, building engines and transaxles. After two or three years we stopped doing assembly work and concentrated on manufacturing, along with research and development.

“In late 1970 we began a crankshaft project in conjunction with Bob Dixon. Bob counterweighted the first VW crankshaft in 1971, and it is still in use today after 96,000 miles in my VW Bus.

“We moved in to a new building in September, 1975 and we have plans for a radical dyna-mometer room. Our latest move is to have new counterweighted crank forgings supplied from Europe by the original air-cooled crank supplier to Volkswagen. They will be available with larger Type 4 main bearing journals. They will also be available with a larger centre main as currently in use in our race engines. We also have raw cast cylinder heads coming from Brazil. We will be able to do as we wish with these, even make 40-hp dual-port heads. With these, we can put the spark plugs in where we want them, as well as the valve guides, and install any size valve seat we wish. They will be available to us with or without the raw ports, but they will have a combustion chamber.

“We are also doing work now on forged alumin¬ium connecting rods, and a lot of transaxle development - that's kind of my thing. As you know, we are working on the five-speed gearbox and hope to have a few available by the World Finals. These ' boxes will also be supplied for the street; it will allow the use of close-ratio gears with an overdrive type 5th gear. And since the fifth gear we use is actually a woodruff key fourth gear, there are nine ratios available for fourth or fifth gear.

“On the engine side, our business keeps increasing on air-cooled VW products, and we have to devote a lot of energy to keep up with it, plus stay ahead in development. We've worked with crankshafts and cylinder heads for the water-cooled VW, but at present there isn’t that much of a market. We’ll stay with it as much as time will allow, though. The aircooled VW market is increasing almost daily and we intend to keep up with it”.

The above piece was condensed from an article published in October 1978.

East Germany’s Finest – They’re Volkswagens!

By Anderer Bleistift

May 1991

With the fall of the iron curtain and German reunification, the local East German Trabants and Wartburgs have become the butt of the world's car jokes. Why do Trabbis have a heated rear window? To keep your hands warm when pushing them. How do you double the value of your Trabant? Fill it with petrol! Chuckle chuckle, but in fact these stinky old cars are very much connected with VW historically, and not only because Trabants now have 1.1 litre VW Polo engines either.

To find out how and why, come with me while we go back in time to before the Second World War.

It was 1928 that Audi, the car company started by August Horch in 1909, was taken over by DKW. This motorcycle company had rapidly expanded during the 1920s, and were attracted by the facilities at Audi's factory at Zwickau in Saxony, in southeast Germany. Their first steam car of 1916 had been called the Dampf Kraft Wagen (Steam Powered Car), and their first two-stroke motorcycle engine was called ‘Das Kleine Wunder’, the little wonder. Hence the DKW name. Up to the start of WW2, DKW were the largest motorcycle manufacturer in the world with factories at Zschopau, Chemnitz and Hainichen, all in Saxony. Their motorcycle success led DKW to manufacture small two-stroke cars at Zwickau for the first time from June 1929. Thus, the first two Auto Union members had amalgamated.

The third auto company, Horch (started also by August Horch in 1899) was also located in Zwickau, and were a natural to join the growing Auto Union combine, which they did in the worsening economic climate of 1931. The fourth member, Wanderer, was also located in Saxony, at Chemnitz, only 12 km from the others at Zwickau, and they joined Auto Union in 1932.

Once Auto Union was established, the emphasis was on integration, and the Audi production was transferred to the Horch plant in 1934. By this time, the only Audi model was the 2-litre Front, an appropriately named front-drive, straight-six cylinder car that did not sell well despite its impressive mechanicals. By contrast, the little front-drive DKWs were going from strength to strength. The 2-seat, 584cc Reichklasse and 4-seat Meisterklasse, both of wood and fabric construction with a Horch-like radiator, together sold nearly 40,000 in 1937 alone.

Thus, in the years up to the start of the war, Auto Union based their success on the tiny two-stroke DKWs, while Wanderer made dependable but unsensational middle class cars. Horch provided prestige with DOHC 3.1 litre straight-eights, flathead 3.5 litre V8s and 6 litre V12 limousines. Audi, by then with experimental 3-litre rear drive straight sixes, were the only weak link in the operation. It's quite ironic then, that the least successful Auto Union concern of the 1930s was the name destined to survive in the post-war years, albeit after a 25-year absence.

All Auto Union marques made contributions to the war effort, as staff cars, transports, army motorbikes and trucks. But the ending of hostilities in 1945 saw the partitioning of Germany, and an Eastern Zone dominated by the Russians. What this meant was an end to all Auto Union's Saxony-based activities, as the area lay within the Russian Zone. The Russians even renamed the city of Chemnitz ‘Karl-Marx-Stadt’.

Horchs, Wanderers and Audis had only been made in small numbers but there were plenty of DKWs in the west, perhaps 150,000 of the little front drive two-strokes. There was a large demand for transport of any kind in western Germany (the reason the Volkswagen plant up at Wolfsburg was kept in operation), and spares for those DKWs was required. Messrs Bruhn and Hahn (father of the current VW Chairman) set up a parts depot at Ingolstadt in Bavaria, and in 1949 Auto Union was registered as a new company in the West. The first car they made was a small delivery van, the Schnell-Laster, with the inevitable front-drive two-stroke layout. By the time the first DKW car produced after the war came in 1950, it was made at a renovated bombed-out factory in Düsseldorf.

This was in fact the pre-war Meisterklasse with the 684cc two-cylinder engine, although with hydraulic brakes and new bodywork. The three cylinder 896cc Sonderklasse arrived in 1953. In 1956 DKW developed the four-wheel drive Munga, a jeep-like vehicle powered by the Sonderklasse's 3-cylinder engine. Popular with NATO and local farmers, it was an ideal cross-country vehicle. It was produced until 1968 and was the last DKW two-stroke with a total of 46,750 having been built.

Anyway, back in East Germany, what was to all intents the DKW Meisterklasse, the ‘F8’, appeared in 1948. It was made by the East German Government-owned ‘IFA’ – the Industrieverband Fahrzeugbau (Industrial Association for Vehicle Construction), at the old Audi factory at Zwickau. The F8 lasted until 1955. In 1950 came IFA's F9 model with 3 cylinder 894cc DKW two-stroke, four years ahead of the West’s DKW Sonderklasse. It lasted until 1956, by which time output had been transferred to the former BMW works at Eisenach and the IFA badge replaced by the new ‘Wartburg’ name. The upgraded car was powered by the 894cc engine initially but was increased to 991cc in 1962. This two-stroke, front-drive DKW descendent slumbered peacefully on and received a modern 1.3 litre Opel engine in 1989. The last Wartburg was made only recently, in April 1991.

Meanwhile, that two-cylinder F8 was replaced in 1956 by a model called the ‘Zwickau’, after its place of manufacture, using the same 684cc twin but with resin impregnated glass/cotton fibre bodywork, the first mass-produced German car to use that material. This continued until 1959 when it was renamed the ‘Trabant’, and given a smaller 500cc motor, enlarged again to 594cc in 1962. It was given the ‘Trabant’ name in honour of the Russian Sputnik satellite of 1959, as ‘Trabant’ in German and ‘Sputnik’ in Russian both mean ‘Fellow Traveller’.

Back in the west, DKW went on to success in the 1950s and was bought by Daimler-Benz in 1958. They persisted with newer two-strokes and body styles into the 1960s, but sales began to slip. When Volkswagen bought DKW from Daimler-Benz in 1965 they were looking for more manufacturing capability for Beetles, but DKW proved Volkswagen's long-term salvation when the DKW name was finally laid to rest and replaced by the resurrected ‘Audi’. They may have dropped the two-stroke, but they kept front-wheel-drive, and the rest, as they say, is history.

And in the East? With the fall of the Berlin Wall in October 1989 VW were very quick to negotiate with Trabant for the replacement of the ancient two-stroke, which produced more than five times the pollution of a modern western car. Trabbis with 1.1 litre Polo engines appeared in April 1990, firstly from western imports but later from local manufacture at the old Zwickau plant. IFA wanted to jointly design a Trabant successor with Volkswagen, but by June 1990 had decided instead to begin local assembly of Polos and Golfs from western SKD kits. Production will be 400 daily by 1992, while Trabbis with Polo engines will continue until the end of this year.

In September 1990 Chancellor Kohl and VW boss Carl Hahn together laid the foundation stone for a new VW plant in Mosel, near Zwickau, to produce Golfs complete at a rate of 250,000 annually. Containing a press shop, bodyshell line, paint shop and assembly line, it will come on stream in 1994. In addition, the old DKW engine plant at Chemnitz is being modernised by VW to produce 420,000 VW engines annually by 1993, creating 35,000 jobs in the process. Another new VW factory is planned for Dresden. VW expects to invest DM3.5 billion annually in eastern Germany for the next five years.

Yes, it's easy to laugh at the ancient Trabants and Wartburgs, but with so much interlocking history it's a surprise and delight to see that they're Volkswagens too.

NSU – Who?

By Anderer Bleistift

July 1991

In a previous Zeitschrift article we chronicled the history of the various Auto Union marques before and after the war, and how the coming of East Germany forced the separation of VW/Audi in the west from Trabant and Wartburg in the east. You'd remember how, in 1928, the small Audi company was taken over by the growing DKW motorcycle concern. Audi's fortunes declined despite DKW's continuing success, and in 1932 they were joined in the new Auto Union combine by the prestigious Horch and the stable Wanderer. These four companies are each represented in today's famous four-ringed Audi badge.

DKW was the sole surviving Auto Union marque to be restarted after the war; Horchs, Wanderers and Audis were no longer made. DKW was again a success in the 1950s but by the time the 1960s came along their time had passed. Daimler-Benz had bought DKW in 1958 but sales slumped under their control, 1964 sales of 78,790 being only half that of 1959. Volkswagen bought DKW from Daimler-Benz in 1965 and immediately began phasing out the old two-stroke designs that had lasted so long. At the same time VW decided to discontinue the DKW name as it was too 'two-stroke' related, and replace it with the 'Audi' name that had been dormant since 1940. The first new Audi was a 1.7 litre car that became the ‘Super 90’ in 1966. 1966 also saw the debut of the Audi 80L and the Audi 60 followed in 1968, all of these cars sharing the same body and suspension.

It was in August 1969 that Volkswagen's chairman, Kurt Lotz, was able to buy the Neckarsulm-based NSU company, and merge them with Audi. Lotz had taken over as VW boss following the death of Heinz Nordhoff, and VW was trying to find a successor to the Beetle. NSU had a few other attractions for VW as well...so who is this NSU anyway?

NSU is actually the oldest of all the players in this story, predating even the four Auto Union marques. They date right back to 1873, when Christian Schmitt and Heinrich Stoll set up a workshop for knitting machines at Reidlingen, on the Danube in southern Germany. Success prompted a move to better premises in Neckarsulm, a town with water-driven machinery at the confluence of the rivers Neckar and Sulm (aren't the Germans logical?) The workshop was called 'Neckarsulmer Strickmaschinen Fabrik', or Neckarsulm Knitting Machine Works.

‘NSF’ diversified into bicycles in 1886; first penny-farthing types but later the newer small wheeled design we know today. Sales grew, and knitting machines were phased out. In 1892 the directors agreed on a new brand name derived from NeckarSUlm, and an NSU trademark featuring stag-horns. Motorcycle production began in 1900, with small 15-hp cars following in 1905.

Following the devastation of the Great War, NSU relied on motorcycle production for survival, particularly during the difficult 1920s. Some good cars were made in these times. The new six-cylinder NSU won the German Grand Prix in 1925 and 1926, but in 1929 automobile production was phased out and NSU sold its new Heilbronn car plant to Fiat.

Motorcycle and moped production kept NSU in business through the 1930s and ‘40s, and in the early 1950s NSU was the largest motorcycle maker in the world. However this changed quickly in the mid 1950s when the first effects of cheap Japanese motorcycles were felt, and their sales declined. In 1957 NSU re-entered the car market with the air-cooled, 600cc two-stroke rear-engined Prinz. There was also a Sport Prinz, and it was a derivative of this, the convertible Spider of 1964, that was the first production car in the world to be powered by a Wankel rotary engine. This rotary system offered a compact, light power unit with only a third of the parts of a reciprocating engine.

Unfortunately, everyone today thinks of the rotary as a Japanese invention, but NSU first became associated with its inventor, Felix Wankel, in 1951. The concept first appeared as a supercharger for a record-breaking motorcycle in 1954, and in April that year NSU decided to press ahead with a four-stroke engine based on the rotary principle. The resulting Wankel engine ran for the first time on 1st February 1957.

NSU's Dr. Walter Froede introduced an eccentric motion to the rotor, and a 1.5-litre single rotor unit powered the two-seat Spider that debuted at the Frankfurt Show of September 1963, just a month ahead of the Mazda Cosmo (which was the result of another Wankel licence). The innovative and pretty Spider remained in production until 1967, but NSU's next project, the Ro80, was far more ambitious. The Ro80 (Ro for Rotary) had a stylish, wind-cheating body (elements of which can still be seen in today's Audis), powered by a 2-litre twin-rotor Wankel, and it was voted Car of the Year on its debut in 1968.

It was unfortunate that the Ro80 didn't live up to its good looks, even though NSU offered extremely generous warranty terms - engine replacement free of charge! You see, although the Ro80 performed very well on the Autobahns, it didn't do so well in traffic jams where the Wankel tended to stall. This exacerbated the problems of an energy absorbing torque converter and power-steering pump, and it was at such times that the vital rotor apex seals, made of ferrous alloy, would suffer excessive wear. This in turn accelerated the already high petrol and oil consumption.

The commitment to the Wankel stretched NSU's finances to the limit, making the company vulnerable to a takeover, which was what Volkswagen achieved in 1969.

NSU was also on the point of introducing a conventionally-engined front drive model, but it was shelved until late in 1970 when it entered production as the Volkswagen K70 (K for Kolben, or 'piston') at a new VW plant at Salzgitter. Sadly, it didn't materialise as the hoped-for Beetle replacement, nor was it parts-compatible with any other VW or Audi in the range, and it was quietly discontinued in 1975.

The Prinz had also been dropped in 1972, so this left the Ro80 as the only NSU left as 1976 arrived. However, the Wankel engine suffered from the post-1973 energy crisis, and its high fuel and oil consumption, coupled with poor exhaust emission performance, outweighed any mechanical or technical advantages. So, finally, in March 1977, VW discontinued production of the pioneering and innovative Ro80 after 37,204 examples had been built.

With it went the NSU name. The spirit of the Ro80 survives today in the equally innovative Audi 100, as does the Neckarsulm plant where Audi 100s are now built. However, it was a sad end for such a striking car, and a courageous auto company.

The Horch and Wanderer Story

By Anderer Bleistift

August 1991

Previously we've looked at the rise of DKW and its acquisition of Audi, then followed the plot as it joined up with Horch and Wanderer to create Auto Union, which was eventually acquired by Volkswagen. Last time we followed the story of NSU, the innovative company that VW merged with Auto Union to form today's Audi concern. The story seems complete, and yet - who were Horch and Wanderer, and why was the old Audi company such a struggler?

To find out, let's go back in time and meet August Horch (1868-1951), born at Winningen on the Mosel River near Koblenz. Son of a blacksmith, he progressed through wagon building to making torpedo boat engines, and by 1896 was managing Karl Benz's Mannheim motor-works, at the time the largest automobile works in the world. However, the innovative Horch was frustrated by Benz's staid approach to engineering, and in 1899 Horch received enough financial backing to start his own motor works.

His first model was a progressive shaft-driven 10-hp horizontally-opposed twin, and by 1902 Horch had a factory in Reichenbach producing 2.5 litre vertical twins. The works moved to Zwickau in 1904, which became the firm's headquarters. This factory was destined to be used later by Audi, then Auto Union, then IFA, then Trabant, then finally Volkswagen today! But I digress. Horch's designs became more adventurous, including 2.7 and 5.8-litre four cylinders, and an 8-litre 50-hp six cylinder in 1907. 1908 saw the development of special Horches with aerodynamic bodies for the Prince Henry Trials of that year. Unfortunately the six-cylinder was a flop, and Horch's continued interest in race specials generated hostility among his co-directors, so much so that in the summer of 1909 Horch left the company that bore his name.

With his departure, the original Horch company foundered somewhat at first, but recovered successfully and by 1914 it had a top-of-the range 6.4-litre four cylinder model capable of 135 km/h, available with an electric starter! Horch designs of the early 1920s were the work of Swiss engineer Arnold Zoller, but in 1923 the experienced Paul Daimler arrived in Zwickau and he introduced the first of a new generation of big straight-eights in 1926 for which Horch became famous. These 3.1-litre, twin overhead cam models, in a great number of variations, sold consistently and built Horch a prestigious reputation. In 1931 new SOHC straight-eights with greater reliability appeared, being the work of engineer Fritz Fiedler who later left Horch to join BMW. In late 1931 the huge 6-litre V12 Horch type 670 appeared. In 1932 Horch joined Auto Union.

Meanwhile, after August Horch had left his original company in 1909 he wasted no time setting up a new business virtually next door to the Horch works, in the name ‘August Horch Automobilwerk’. Not surprisingly, his former associates weren't very happy about a newcomer with the same name, and they obtained a court injunction forcing Horch to drop the name. In a gesture of defiance he simply translated his surname into Latin on the suggestion of his son, and the matter was resolved. You see, ‘Horch’ in German means ‘hark’ or ‘listen’, and the Latin equivalent is ‘Audi’. The correct pronunciation of this word rhymes with ‘Howdy’.